Soft Power, an exhibition of textile art now running at Tacoma Art Museum opened October 14, 2023 and runs through September 1, 2024 and offers an expansive, colorful and provocative experience.

Had we world enough and time, a person could no doubt write a whole book exploring the many facets of this one show. One might, for example, explore the whole history of textile arts, clearly one of the original creations of humankind. We could examine how different textile traditions have developed in widely different cultures from the beginning right up to the present. We might want to look at what role gender has played in the development and production of textiles in an array of cultures and determine whether spinning and weaving has always been traditionally categorized as “women’s work.”

Given some claims made in TAM’s descriptions of the show, we might want to debate whether or not textile as a medium has always been relegated to a second-class status, given that there are phases in the history of Western Civilization in which textiles, especially tapestries, have enjoyed pride of place right up there with painting and sculpture.

We could go on to talk about the ways in which feminist artists of the 1960s and ‘70s deployed textile art as a means to break into the heretofore male dominated fortress of the art museum. From there we might ponder whether or not the work of these pioneering feminist textile artists were so successful that the idea of resistance is now woven into the DNA of the medium.

After all of that, the book about the show might go into a long, philosophical discussion on the show title, Soft Power, which is taken from the title of a book by international affairs theorist, Joseph Nye, who asserted that “soft power” is the attractiveness of American culture to people from around the globe. Use of the term “soft power” for the show title is thus somewhat ironic in that most of the artists in the show — judging from commentary in their statements and the wall tags — are to greater or lesser degrees, acting as critics of American culture. (So much so that one can imagine a figure like Florida governor Ron Desantis exploding like a volcano over the level of what he would call “wokeness” extant in the literary content of the exhibition.) (Art exhibits are as much about the interpretation of the work provided by the auxiliary verbiage that stands next to the artwork — like commentaries in the margins of a sacred text — as they are about the art itself).

And then there are the artists themselves to engage with. Any group show is a Whitman’s Sampler of artists, each contributing just a small amount of their work. But these are accomplished, dynamic artists, each involved in an ongoing dialogue with their own work. What the museum visitor sees is just the tip of the iceberg of the body of the work of each artist. One could spend a good long time doing a deep dive into the lives of the artists, and going on to find more and more examples of their work, tracking how it evolves over time.

Alas, this article is written for a periodical. And periodicals are not scholarly, art history tomes, nor are they philosophical essays. And so, we must content ourselves here with a quick overview of the show and a dab of commentary on just a few of the 21 artists in the show. Those who are intrigued will then have to engage with the show themselves and delve into those aspects of it that they find worthwhile.

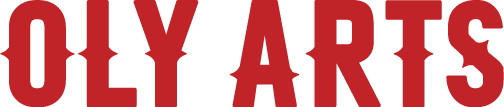

Walking into the large gallery space in which the exhibition is housed, viewers are confronted with a dazzling array of color, image and texture. There is a compelling sense of vitality. It looks like a wonderland, a playground, or a jungle right out of H. R. Pufnstuf. The eye is drawn to a soaring screen made of fabrics knit by a vintage machine (“Daylights” by Allyce Wood), to a gigantic green carp kite (“Koinobori” by Erika Harada), to a big bloated tiger with red silk tassels (“War Baby” by Nina Vichayapai). And right in the middle of it all is a megalith covered in strips of cloth, which visitors are invited to contribute to, using swatches of cloth, yarn and other textiles provided.

Lily Martina Lee’s series of death shrouds, which occupy a back corner of the gallery, are more muted in terms of color, but the story they tell is compelling. The artist wove death shrouds for some of the many deceased women whose remains are found in the western landscape. Lee researches the public record for each case and visits the site where each woman was found, taking a picture of the shroud laid in place. Each of the eleven shrouds in the exhibit is accompanied by a photo of place and some information about what is known of the woman for whom the shroud is made. “Each shroud,” writes Lee, “incorporates information about the women into the structure of its pattern.” To those who stand and engage with the photographs, and the shrouds in this corner, the reward is a sense of the lonesome tragedy of each death, blended with admiration for the sympathetic and poetic way in which the artist pays homage to these individual women.

On the back wall, Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes’s assemblages of vintage clothing have an almost supernatural presence. The central piece, “Assumption U,” is like unto an angelic being with three embroidered tiger patches for a head, a letterman’s jacket from Assumption University for a torso, sexy gold lame’ basketball shorts for a pelvis and a pair of vintage Nike shoes for feet. Alley-Barnes lists things like unguents, incantations and antique filaments and fibers as some of the media used in his works. There is even a blood stained, turn of 19th century Hudson’s Bay blanket in the mix. Where does he find this stuff that he turns into something like a giant surrealist altar piece? One could spill a lot of ink in a discussion of Alley-Barnes’ work as it has developed over time and how that is linked to his personal story (which involves a violent encounter with the Seattle Police.)

Tuan Nguyen’s “Skin” is wonderful in its macabre humor and its personal intimacy. The piece features some of the artist’s t-shirts, cut so as to resemble animal skins draped on a wooden rack. In the midst of these is one made to resemble (in a cartoonish way) the skin of a human, covered in tattoos. It brings to mind old icons of St. Bartholomew, who is depicted holding his own skin at the last judgment.

In conjunction with Soft Power, TAM is presenting a monthly film series called Filament billed as “a moving image series conceived in dialogue with the exhibition Soft Power.

Elsewhere in the museum there are a variety of other exhibits including “Momentum: New Work in the Collection,” which runs through May 26. “Painting Deconstructed: Selections from the Northwest Collection” is on extended view.

Also on permanent display are TAM’s collection of studio jewelry art and Chihuly glass.

Upcoming exhibits include [re]Frame: Haub Family Collection of Western Art, opening May 18.

What:

Soft Power

When:

Through September 1, 2024

Where:

Tacoma Art Museum, 1701 Pacific Ave., Tacoma

Learn More:

tacomaartmuseum.org, 253-272-4258

Cost:

Free every Thursday 5-8 p.m., otherwise $18 adults, $15 seniors and military, $10 youths (6-18), Members free, see website for discount programs.